CSDDD for companies: The EU law at a glance

Supply Chain (CSDDD & LkSG) - Reading time: 15 Min

The Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) is a new EU directive. It obliges companies to take a careful look at human rights and the environment along the entire value chain. In concrete terms, this means that companies must systematically review and manage their supply chains in order to identify, prevent and minimize risks such as human rights violations or environmental damage. The CSDDD Directive is considered an important step towards sustainable corporate governance in Europe and beyond. This is because it goes beyond mere reporting obligations and places greater emphasis on effective management processes, clear responsibilities, monitoring and enforcement. This overview explains the requirements of the CSDDD, which companies are affected, how implementation and monitoring work, what deadlines apply and what opportunities and risks arise.

The most important facts about the CSDDD

The CSDDD is an EU directive that obliges large companies to fulfill human rights and environmental due diligence obligations along their entire value chain, both within and outside the EU.

It aims to ensure that companies identify, prevent, mitigate and account for negative impacts on human rights and the environment. It also promotes sustainable and responsible business practices in line with the Paris Climate Agreement.

- From July 26, 2028: EU companies with > 3,000 employees and > € 900 million global net sales and non-EU companies with > € 900 million net sales in the EU.

- From July 26, 2029: all other companies covered (including > 1,000 employees and > € 450 million turnover or corresponding EU turnover for non-EU companies).

- It has been politically agreed to limit the CSDDD to > 5,000 employees & > €1.5 billion in future and to launch it from July 2029 (not yet finalized by the EU Commission).

Companies must identify risks relating to human rights and the environment in their own business areas, at subsidiaries and along the supply chain. They must also take appropriate measures to prevent or minimize them.

Yes, large companies are obliged to draw up and implement a transition plan towards climate neutrality by 2050. It must also be in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

The implementation of the directive is monitored by national authorities. Violations may result in sanctions, including fines and civil liability.

It strengthens the transparency and responsibility of companies, promotes sustainable business practices and creates a level playing field within the EU.

Summary: CSDDD at a glance

The CSDDD (Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive) is the EU directive for human rights and environmental due diligence obligations in supply and value chains. It requires not only reporting from large companies, but also a permanently functioning management process. This includes identifying and prioritizing risks, taking effective preventive action, facilitating remedial action and providing verifiable evidence of its effectiveness.

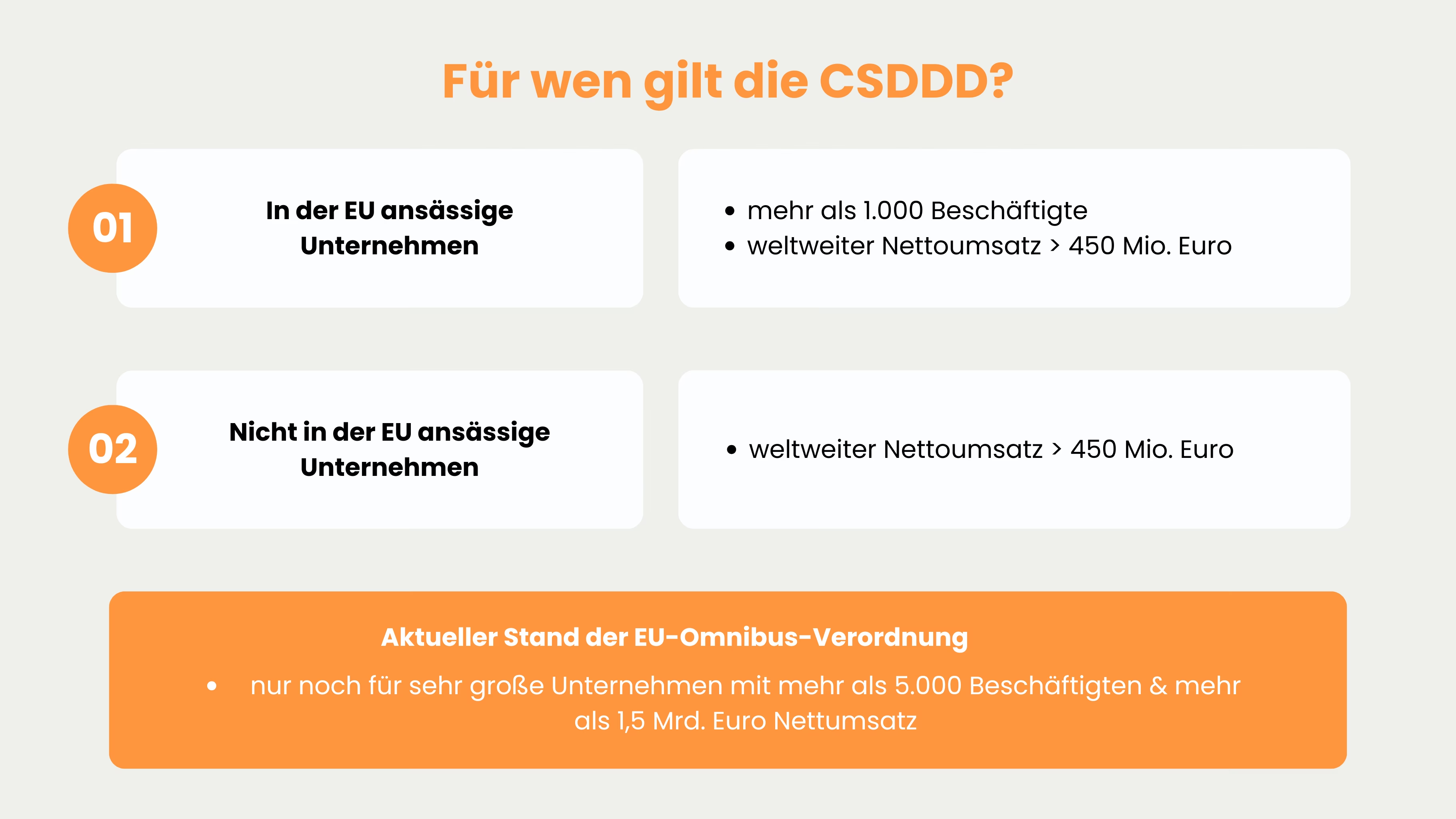

According to the current directive, EU companies with more than 1,000 employees and a worldwide net turnover of more than 450 million euros are subject to the directive. For non-EU companies, the turnover achieved in the EU is decisive. The threshold of more than 450 million euros is also relevant here. In addition, certain franchise and licensing models can be covered if defined turnover and fee thresholds are exceeded. SMEs are usually not directly affected, but are often indirectly involved because large companies demand proof and standards along the supply chain.

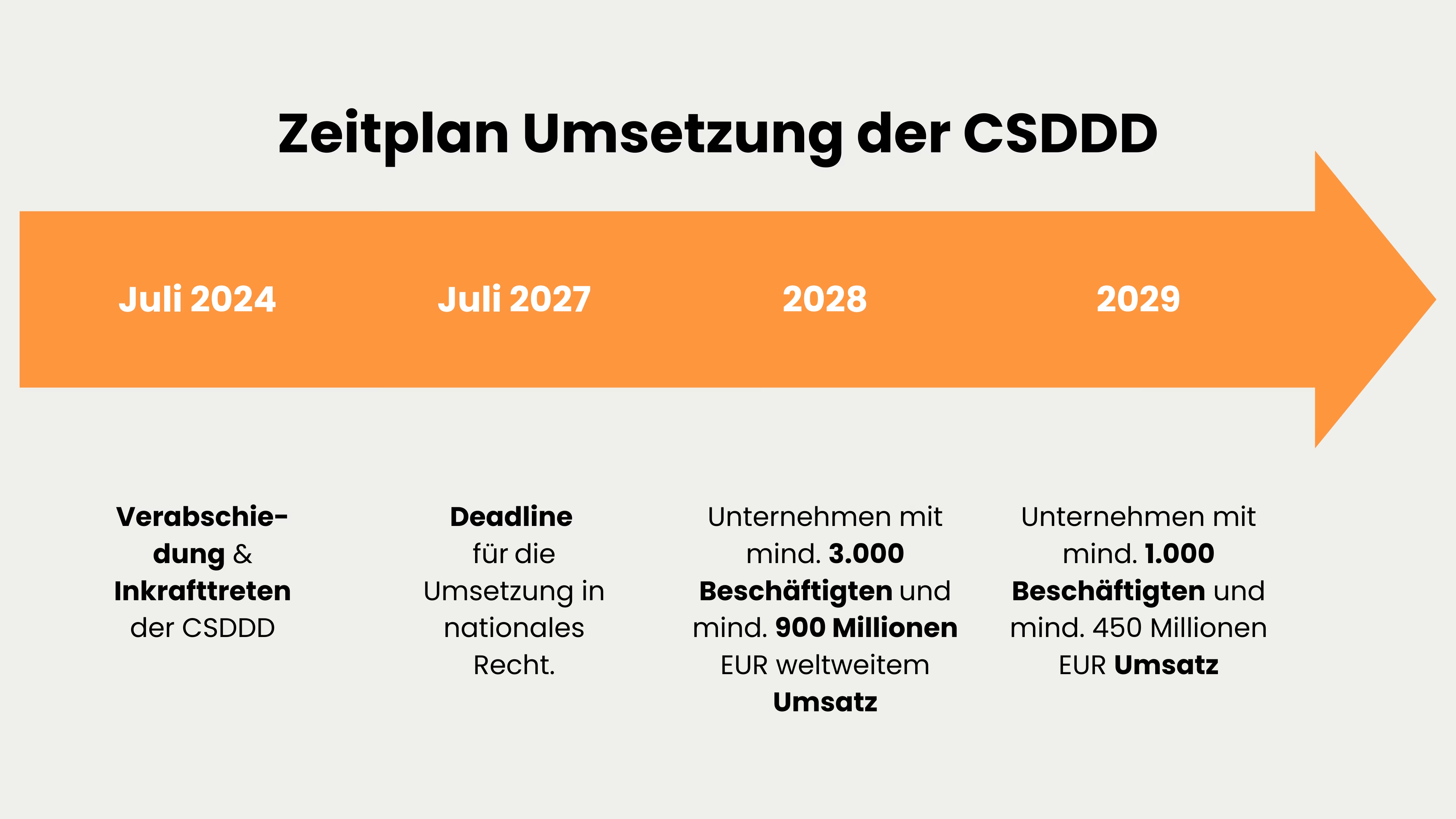

The CSDDD came into force on July 25, 2024. Due to the European Union's "stop-the-clock" approach, national implementation is currently scheduled until July 26, 2027. Application will start in stages from July 26, 2028 and is expected to take effect across the board from July 26, 2029. At the same time, the EU omnibus procedure and a further postponement, including a narrower scope of application, are currently being discussed. However, this will only become legally binding after final political approval.

The core obligations are a risk-based risk analysis and prioritization, a graduated program of measures (prevention, mitigation, remediation), a secure and accessible complaints mechanism, ongoing monitoring and robust documentation. The obligations relate to the "chain of activities": own activities and subsidiaries and, in particular, upstream supply chain stages and certain downstream activities (e.g. transport/storage) - each prioritized according to risk. For large companies, the current text also provides for a climate transition plan. This point is in flux in the omnibus process.

National authorities are responsible for monitoring compliance with the directive. To this end, they request information, initiate investigations and order measures to be taken. External stakeholders can also submit substantiated concerns. Violations can result in fines, official orders and considerable reputational pressure for the company. The current text also includes a liability framework, which is also the subject of political debate.

Until German implementation, the LkSG remains decisive for affected companies. At the same time, it is worth setting up processes in such a way that they reflect the LkSG and CSDDD in an integrated program. Starting early reduces operational risks, stabilizes supply chains and improves market access, financing and stakeholder confidence.

Latest news on the CSDDD in relation to the EU omnibus package

The Omnibus I package has clearly shifted the direction of the CSDDD: less "one-size-fits-all", more focus on very large companies and a significantly leaner administrative logic - without completely abandoning the goal of due diligence obligations.

1) Significantly narrower scope: CSDD obligations only for very large companies

According to the political deal reached in December 2025, the due diligence obligations will only apply to very large companies in future: more than 5,000 employees and more than € 1.5 billion in net turnover (including corresponding non-EU companies with turnover in the EU above the same threshold). This is a noticeable reduction in the number of companies directly subject to the obligation.

2) Risk-based approach instead of full coverage - focus where it really "burns"

In terms of content, the focus is more on a risk-based approach. Companies should intensify their due diligence measures along their supply chain, especially where negative impacts on human rights or the environment are most likely. The expectation is thus moving away from the idea of "screening" every single stage of the supply chain across the board. At the same time, it remains clear that if there are objective and verifiable indications of problems, a company must also take a closer look. The risk-based approach is therefore not a free pass, but a prioritization.

3) Less "trickle-down": smaller business partners should not be overwhelmed with requirements

A central motive of the omnibus deal is to ensure that obligations and information requirements do not "slip through" to smaller companies in an uncontrolled manner. Companies in scope should not demand unnecessary information from companies that are not covered themselves. In practice, this means that data requirements must be more proportionate and targeted. If this does not happen, they will quickly become a bureaucratic project.

4) Less frequent reviews: Review typically only every five years

Due diligence measures are to be reviewed and adjusted much less frequently in future. The plan is to review them only every five years - unless there are concrete indications that the measures are no longer appropriate or effective. This will ensure more predictable cycles and reduce permanent "continuous operation".

5) Climate transition plan: deleted from the deal (not just postponed)

Important for the classification: According to the EU Parliament text, companies in the scope should no longer have to prepare a transition plan for Paris compatibility. This is a real relief in terms of content.

6) Liability remains national, fines possible

The direction is also clear here: less EU-wide standardization, more leeway for national rules. Civil liability should therefore not be regulated uniformly at EU level. Nevertheless, sanctions remain possible, for example fines of up to 3% of global net turnover.

What is the CSDDD? Objectives and significance of the EU directive

Background and development of the CSDDD

The CSDDD(Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive) is based on the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. For a long time, companies have mainly relied on voluntary standards. At the same time, many different national supply chain laws have emerged in Europe. With the CSDDD, the EU is now creating a uniform and binding framework for corporate due diligence obligations.

What is important is that it is not about "even more reports", but about better risk management in everyday life. While the CSRD primarily regulates how companies report on sustainability, the EU Supply Chain Act focuses on implementation. Companies should systematically identify, prioritize and manage risks and negative impacts on human rights and the environment along their value chain. This includes identifying risks at an early stage, preventing or reducing them, ending damage and, if necessary, enabling remediation and redress. The approach is therefore clear: away from one-off checks and selective audits and towards a permanent, risk-based process.

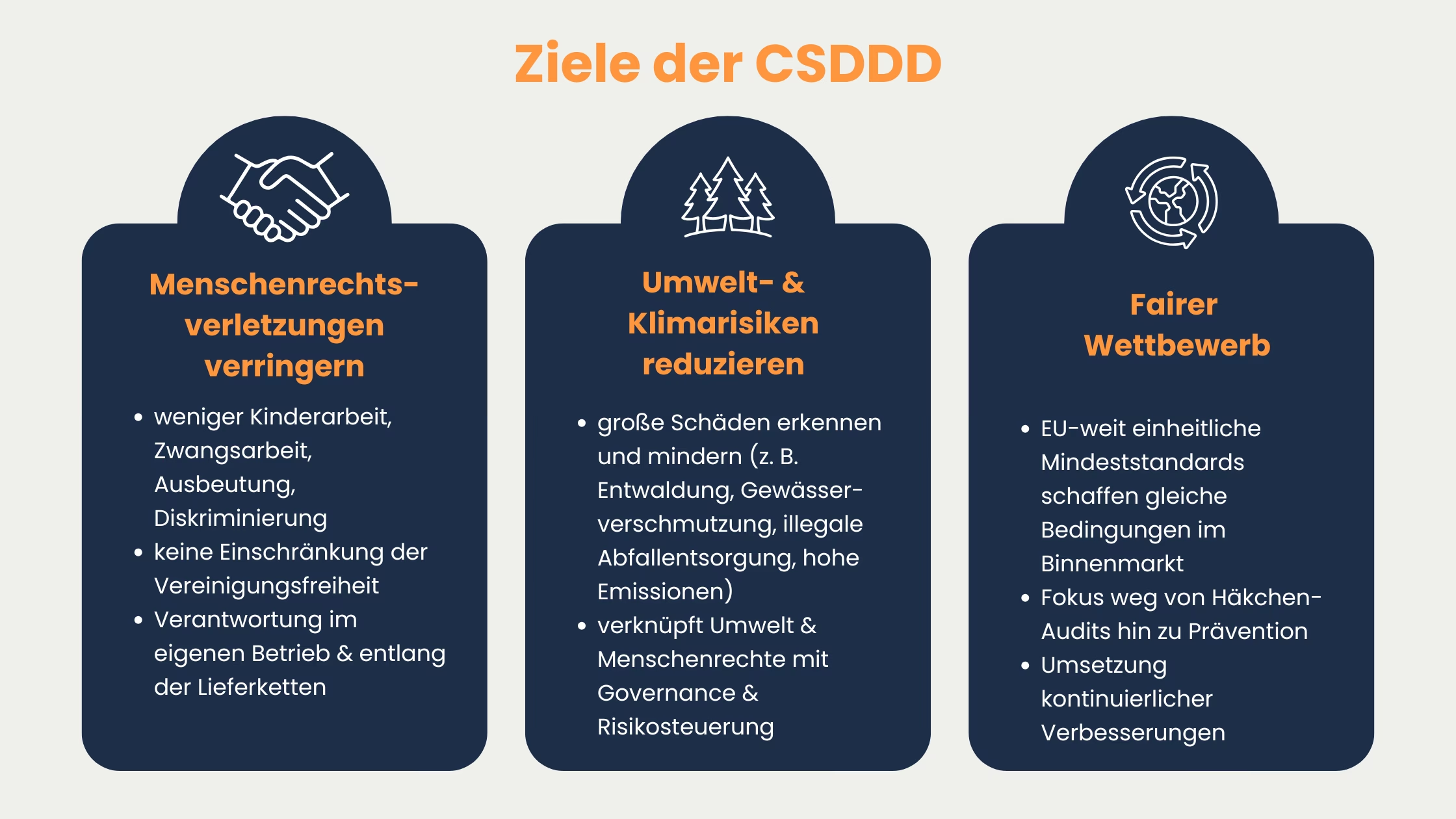

Objectives of the guideline for sustainable corporate governance

Its main aim is to ensure that serious human rights violations in global supply and value chains become less frequent. These include, for example, child labor, forced labor, exploitative working conditions, discrimination or restrictions on freedom of association. Companies therefore have a greater obligation. Not only in their own operations, but also where they can exert influence through suppliers and partners.

Secondly, it is about environmental and climate risks. The directive is intended to help identify and reduce major environmental damage at an early stage. For example, deforestation, polluted waters, illegal waste disposal, loss of biodiversity or highly polluting emissions. The CSDDD thus links environmental and human rights objectives with clear expectations of corporate management and risk control.

Thirdly, the CSDDD Directive is intended to ensure fairer competitive conditions in the EU internal market. Standardized minimum requirements prevent companies that already act responsibly from being put at a disadvantage compared to less ambitious competitors. Overall, the focus is shifting. It is moving away from pure PR measures and tick-box audits towards genuine prevention, implementation and continuous improvement.

Significance of the EU Supply Chain Act for the environment, human rights and companies

The CSDDD commits companies to more sustainable supply chains. It aims to make global supply and value chains more transparent and responsible. If companies systematically identify and manage risks, serious human rights violations and environmental damage are more likely to be avoided. At the same time, the directive addresses a growing expectation: Many people want to know where products come from and under what conditions they were manufactured.

For companies, this initially means more effort, for example through clearer responsibilities, better documentation and more reliable data from the supply chain. However, this can pay off in the long term: Good due diligence and risk management makes supply chains more stable, reduces failures and strengthens trust among customers, investors and partners. Those who understand CSDDD as part of management become more resilient and better able to plan.

Which companies are affected by the CSDDD?

Industries and size criteria

Which companies are covered by the EU Supply Chain Act depends primarily on size and turnover, not on a specific sector. According to the current text of the directive, large corporations and comparable companies in the EU are generally covered if they have more than 1,000 employees and a global net turnover of more than 450 million euros. For non-EU companies, the directive applies if they generate more than EUR 450 million in net turnover in the EU. The decisive factor is therefore the turnover achieved in the EU, not whether there is a local branch or subsidiary.

Franchise and license models may also be covered: If franchise or license agreements in the EU ensure a uniform identity and a uniform business concept and certain thresholds for turnover and royalties are exceeded (including > €80 million net turnover and > €22.5 million royalties), this model may also fall within the scope of application.

Important in practice: Even though the directive applies to all sectors, the risks vary greatly depending on the sector. In areas such as textiles, agriculture, construction, raw material extraction, electronics or logistics, there are often more human rights and environmental risks, particularly due to complex supply and subcontractor chains. In many services, on the other hand, the focus is more on working conditions, outsourcing and subcontracting chains.

Current omnibus status: A provisional political agreement has been in place since December 9, 2025, which would narrow the scope of the CSDDD to very large companies (threshold: 5,000 employees and 1.5 billion euros net turnover). However, until this amendment is formally adopted, the text of the directive described above will continue to apply.

Different requirements for SMEs and large companies

As a rule, SMEs are not directly subject to the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. This applies as long as they do not exceed the threshold values. In practice, however, many are indirectly affected: Large companies that fall under the directive often demand additional information, standards and evidence from their suppliers. This is done, for example, through purchasing conditions, codes of conduct, contracts, training or risk-based monitoring. At the same time, the EU framework provides for smaller companies to be supported and not overburdened. As business partners in supply and value chains, they are often dragged along without being directly regulated themselves.

Timetable: When will the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive come into force?

Planned date and transition periods

The CSDDD was published in the Official Journal on July 5, 2024 and entered into force 20 days later, on July 25, 2024. Originally, the EU member states were supposed to transpose the directive into national law by July 26, 2026. However, this deadline was postponed by one year due to the "Stop-the-Clock" Directive (EU) 2025/794: It must now be transposed into national law by July 26, 2027.

The material obligations are generally staggered in the current text of the Directive: first for very large companies and then for other size categories. It is important to note that for group structures, the decisive factor is regularly how the relevant thresholds are to be examined at group level or in accordance with the requirements of the directive. For non-EU companies, the turnover generated in the EU counts. This applies regardless of whether there is a subsidiary or branch in the EU.

Current status of changes to the EU omnibus: Since December 9, 2025, there has been a provisional agreement between the Council and Parliament that would push the timetable back again: The implementation deadline would then move to July 26, 2028. Companies would have to comply from July 2029. This adjustment has been politically agreed, but has not yet been finalized as a final legal act.

Important milestones and deadlines

According to the current legal status (stop-the-clock already effective):

- July 2024: Entry into force of the CSDDD (Directive (EU) 2024/1760).

- July 26, 2027: Latest national implementation in the EU member states.

- From July 26, 2028: Staggered start of validity for very large companies

- EU: > 5,000 employees and > €1.5 billion in global net sales

- EU: > 3,000 employees and > €900 million global net sales

- Third countries: corresponding EU turnover thresholds in each case

- From July 26, 2029: Staggered start of validity for the "residual scope"

- EU: > 1,000 employees and > €450 million global net sales

- Third countries: > €450 million turnover in the EU

- Franchise/Licensing: including > €22.5 million in royalties and > €80 million in sales

If the omnibus agreement is finally implemented in this form:

- Scope will be significantly narrowed: due diligence obligations will only apply to companies with > 5,000 employees and > €1.5 billion net turnover (including third-country companies with EU turnover above the threshold).

- Transition plan not applicable (deleted in the deal).

- Timetable: expected new implementation and application dates (frequently mentioned: implementation by 2028, application from 2029). The final legal texts and national implementation are decisive.

For Germany, this means that the CSDDD is likely to be implemented via an amendment or further development of the LkSG and supplementary regulations. Companies should therefore not just base their planning on a deadline, but should set themselves a roadmap with clear annual targets. For example, for risk analysis, a program of measures, a complaints mechanism and contract and supplier management. This way, the processes are ready to go as soon as the relevant wave of implementation takes effect.

Obligations of the CSDDD for companies

General requirements for corporate due diligence

The EU Supply Chain Act requires a risk-based due diligence process that is based on the UN Guiding Principles and the OECD Guidance. This is not a one-off project, but a permanent management process. Companies should identify, prioritize and address the most important risks and negative impacts on human rights and the environment. This should take place in their own business, at subsidiaries and along their due diligence and supply chain.

These include:

- Preventive measures to prevent damage, and

- Remedial measures if something has already happened.

Clear responsibilities, fixed deadlines and measurable targets are important here. These are often bundled in an action plan that manages risk reduction step by step.

A central component is a well-functioning complaints procedure. Employees, business partners and affected persons should be able to provide reliable information. This allows problems to be identified at an early stage and resolved more quickly. Companies must also regularly check whether their measures are actually working, adapt the process if necessary and document everything in a comprehensible manner. Transparency and reliable evidence are always important. Here you will find information on our whistleblower system, which can be used to implement such a complaints procedure.

Good management includes a clear due diligence policy. This should state how risks are prioritized, who is responsible for what and which goals are to be achieved. It is also important that the topic is visibly anchored in management. In addition, the applicable policy text for large companies provides for a climate transition plan. This plan should show how the business model and strategy can be made compatible with the 1.5°C target and EU climate neutrality and how the company will implement this step by step.

Topicality note: In the omnibus procedure, it has been politically agreed to delete this climate plan obligation. However, only the final adoption of the amendment is legally binding.

Finally, practical implementation also includes accountability: Companies must be able to demonstrate how they implement due diligence obligations. Typically, this is done via publication in a sustainability report or via information on the company website (depending on national implementation and integration with other obligations).

Integration of due diligence into corporate processes

It is important that due diligence obligations are not run as a "CSR side project", but are firmly integrated into everyday life. This means, for example, that purchasing evaluates suppliers not only according to price, quality and deadlines, but also according to ESG criteria. This includes a risk-based selection, appropriate requirements depending on the risk and clear steps on what happens in the event of problems.

Product development and engineering can also reduce risks at an early stage, for example through the right choice of materials, good chemical management, reparability and recyclable design. Compliance and Legal ensure that standards are uniform, for example through codes of conduct, contractual clauses and remediation rules. And Risk Management and Internal Audit regularly check whether the measures really work in practice.

HR and occupational health and safety are also key. Not only in the company's own operations, but also in temporary work, contracts for work and subcontractor chains, where risks often arise. The finance function links targets and measures with budgets and investment decisions. It supports scenario analyses and shows where risks can cause long-term costs. IT provides the necessary infrastructure: risk screenings, supplier portals, documentation, whistleblower systems and evaluations.

In short: CSDDD only works if responsibilities are clearly distributed, data flows are in place and the control system is effective on a day-to-day basis. Then "duty" becomes a robust system that recognizes risks early on, reduces damage and makes processes easier to plan.

Due diligence obligations under the CSDDD: What companies need to consider

Risk analysis and prioritization

The CSDDD does not require a "full audit" of the entire supply chain, but rather an appropriate, risk-based approach. The focus is on the question: Where are the most serious and most likely negative impacts and where can we exert an effective influence?

Prioritization is based on severity, probability of occurrence and remedial options. A step-by-step approach has proven itself in practice:

- Scoping / mapping: Identify countries, sectors, product groups, materials, processes, subcontract chains.

- Risk assessment: Creation of a heat map with internal data (spend, supplier structure, locations) plus external sources (country/industry indices, NGO reports, media, studies, official information).

- Deepening for hotspots: Where the risks are high, supply chain sections are examined more granularly (e.g. specific locations, subcontractors, raw material sources).

- Regular updates: Risk analysis is not an annual ritual, but is adapted in the event of changes (new countries, new suppliers, incidents, M&A).

Examples of typical risk hotspots:

- Textile: cotton origin, spinning mills, dyeing/wet processes, waste water/chemicals, overtime.

- Electronics: 3TG raw materials (tin, tantalum, tungsten, gold), working conditions in production, chemicals.

- Construction/facility/logistics: subcontract chains, occupational health and safety, migrant labor, working hours.

- Agriculture/commodities: deforestation, pesticides, wages, land rights, water consumption.

Important: The prioritization must be plausibly justified and verifiable.

Measures: Prevention, mitigation and remediation

The prioritization results in a package of measures. This is not a case of "everything for everyone", but is graded according to risk. An impact is created above all when measures address certain root causes (e.g. unrealistic delivery times → overtime).

Typical measure modules

- Supplier Code of Conduct and clear requirements per product group and risk

- Contractual cascades (passing on obligations, audit rights/transparency, remedial mechanisms)

- Training & capability building (for purchasing, suppliers, subcontractors)

- Improvement plans (CAPs) with deadlines, responsible parties, measurable targets

- Incentive systems: more long-term acceptance, realistic lead times, fair pricing, bonus/malus

- Independent verifications where the risk is high (not comprehensive)

- Immediate measures to stop the damage

- Remediation plans (e.g. back pay, safe working conditions, access to grievance channels)

- Cooperation with local players (trade unions/NGOs/industry initiatives)

- If no improvement can be achieved despite measures, companies must reduce the risk step by step. In extreme cases, this may even mean terminating the business relationship. The approach should be proportionate and take into account the possible consequences for local employees.

Depending on the topic, environmental and climate risks can be reduced in a targeted manner with specific programs. For example, by using fewer hazardous chemicals, better wastewater treatment and less waste. More circular models, deforestation-free supply chains and forest protection can also be effective. In addition, programs for renewable energies and greater energy efficiency among suppliers can also help.

On the climate transition plan: The current CSDDD text provides for it for large companies. In the omnibus package, it was politically agreed to remove this obligation. However, this is only binding once the amendment has been finally adopted. In practice, many companies continue to plan with it anyway, because customers and investors often expect such plans anyway.

Supply chain: scope, monitoring and cooperation

The CSDDD applies to the chain of activities, i.e. to the company's own business, subsidiaries and, above all, the upstream steps in the supply chain (raw materials, processing, production). On the downstream side, transportation, storage, distribution and certain end-of-life issues (e.g. take-back or disposal) may also be relevant, depending on the case. The pure use of the product, on the other hand, is usually not the focus.

It is important to note that responsibility does not automatically end with the direct supplier. If the greatest risks lie further down the chain, companies must also take them into account for indirect suppliers on a risk-based basis.

Monitoring: "data-based instead of audititis"

Appropriate monitoring combines different data sources, depending on the risk:

- Supplier self-disclosure (structured, verifiable)

- Certificates and standards (only as a building block, not as a free pass)

- Audit reports and assessments (risk-based, targeted)

- Complaints and incidents

- Public sources, media, NGO reports

- Environmental and geodata (e.g. satellite data on deforestation), measurement data (wastewater/emissions) where available

- Digital traceability approaches (material flow analyses, traceability, perspective product fit logics)

Cooperation as a lever

Sustainable change rarely succeeds alone. They are often effective:

- Industry initiatives and multi-stakeholder standards

- Joint training programs and tools

- Remediation funds or jointly financed remediation projects in high-risk regions

- Coordinated requirements so that suppliers do not have to use 20 different questionnaires

Grievance mechanism and accountability

An effective complaints mechanism is key because it makes risks visible that often do not appear in data and audits. It should be secure and confidential, easily accessible, even for those affected outside the EU, and offer protection against reprisals. There also needs to be a clear procedure for reviewing, escalating and implementing concrete remedial action. It is also important that the knowledge gained is systematically fed back into the risk analysis and into action programs.

Transparency includes robust documentation and an understandable public presentation of what a company is doing and how effective the measures are. For companies covered by the CSRD, there are synergies because due diligence content can be integrated into ESRS reporting.

However, the clear separation remains crucial: the CSDDD requires effective processes and remedial action, while the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) structures reporting.

Monitoring and enforcement of the CSDDD

Competent authorities and control mechanisms

The CSDDD is primarily enforced by national supervisory authorities. Each EU member state appoints one or more authorities to check whether companies are complying with the national implementation rules. These authorities are more than just contact points: They can initiate proceedings, request information and order specific measures. To ensure that this also works in cross-border cases, a network of supervisory authorities is also planned at EU level to support cooperation and coordination between countries.

What is particularly important in practice is that the directive creates a clear way of submitting reports. Both private individuals and organizations can report substantiated concerns to the supervisory authority if there are objective indications of violations.

Tests and audits

The supervisory authority will generally work in a risk-oriented manner. This means that companies will not all be subject to the same level of scrutiny, but rather depending on the sector, specific incidents, risk profile and the quality of the evidence submitted. The directive also requires that the authorities have sufficient powers, among other things:

- Requests for information and submission (documents, data, evidence)

- Investigations, also ex officio or on the basis of substantiated indications

- On-the-spot checks / inspections (if necessary with the support of other Member States)

For companies, this means that certificates and social audits can provide support, but they are no substitute for a robust system. Companies are expected to evaluate audit programs realistically, know their limits and combine several sources. In practice, this means that evidence from audits, the complaints channel, internal key figures and external information must be combined in order to truly identify and effectively manage risks.

Role of the EU and national authorities

At EU level, guidelines and practical tools should ensure that the CSDDD is implemented and enforced as uniformly as possible in the Member States. This should prevent the development of 27 very different interpretations. Nevertheless, the details in practice will have a strong national character, for example in terms of responsibilities, depth of checks, priority checks and cooperation with other authorities.

What is particularly important for companies is that the directive rarely stands alone. It often works together with other regulations, for example the Deforestation Regulation(EUDR), the Battery Regulation or the Chemicals Regulation (REACH). It is therefore worthwhile to draw up integrated requirements: A common risk and data basis that serves several obligations at the same time is more efficient than parallel isolated solutions.

Sanctions for breaches of EU law

Types of sanctions: Fines and other measures

In the event of violations, the CSDDD primarily provides for administrative sanctions by the national supervisory authorities. The fines are to be based on the company's global net turnover. The member states must also set an upper limit for fines. This maximum fine can amount to at least 5% of global net turnover.

In addition to fines, authorities can issue specific orders to remedy violations. These include

- Requirements to improve certain processes (e.g. risk analysis, preventive measures, monitoring),

- the implementation of clearly defined remedial steps within a deadline,

- Obligations to provide evidence and report to the authority as part of the inspection.

Transparency and publicity create additional pressure. Authorities can publish decisions and findings, which quickly leads to an effect such as naming and shaming. This can be very stressful for companies, often regardless of how high the actual fine is.

CSDDD compliance can also play a role in the public sector. Depending on national implementation, sustainability and compliance requirements can be incorporated more strongly into procurement procedures, for example as a suitability criterion or as a contractual condition.

CSDDD current status incl. omnibus: In the deal of December 9, 2025, it is planned to cap the maximum fine at 3% of global net turnover. However, until the final adoption of this amendment, the text of the Directive will continue to apply.

Reputational risks and legal consequences

In addition to regulatory control, the CSDDD can also have consequences under civil law. Under certain circumstances, companies can be held liable for damages if their own breach of duty has contributed to this. It is important to note that liability does not automatically arise simply because a business partner has caused damage. The decisive factor is the company's own misconduct or failure to take appropriate measures.

The directive also strengthens access to justice. Member states should ensure that such claims do not expire too quickly (at least five years) and that those affected can assert their rights in practice, in some cases with the support of trade unions or NGOs.

Reputational and business damage is at least as important. If serious incidents become public, this can severely damage customer relationships, investor confidence and an employer's image - often more than a fine. A robust due diligence system therefore has a double effect: it reduces the risk of incidents and ensures that decisions and measures can be clearly documented in the event of an emergency.

Omnibus update: Politically, it is planned to withdraw or delete the EU-wide harmonized liability regime. However, this will only be binding after final adoption.

Differences: CSDDD vs. LkSG

Similarities and differences between the two laws

The German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (LkSG ) and the EU Supply Chain Directive follow the same basic principle: risk-based due diligence obligations instead of a full audit "at any price". At their core, both require a regular risk analysis, appropriate preventive and remedial measures, a complaints procedure and comprehensible documentation.

The differences lie primarily in the scope and legal consequences. The CSDDD sets an EU-wide minimum standard, while the LkSG is a national law with German supervisory practice. The scope of application also differs: the LkSG has applied to companies with at least 1,000 employees in Germany since January 1, 2024, while the CSDDD is based on EU-wide thresholds. In terms of content, the EU law is also broader because it incorporates environmental and biodiversity aspects to a greater extent and addresses significant environmental impacts more comprehensively than the LkSG in practice.

Another difference concerns climate issues and liability: the current CSDDD text provides for a climate transition plan (Art. 22) and civil law elements. There is no direct equivalent in the LkSG. At the same time, these points are in flux due to the omnibus procedure: Politically, it has been agreed to remove the climate plan and reduce the EU-wide harmonized liability. However, this will only become binding after final adoption.

Differences in scope and obligations

The differences can be seen above all in how far due diligence obligations extend in the supply chain. The LkSG focuses primarily on direct suppliers and usually only takes a closer look at indirect supply stages if there are specific indications of risks. The CSDDD, on the other hand, works with the "chain of activities" and requires a more structured, risk-based view beyond the direct stages.

In addition, unlike the LkSG, the CSDDD can also cover franchise and license models under certain thresholds. There are also differences in enforcement: In Germany, the Federal Office of Economics and Export Control (BAFA) monitors the LkSG, while the CSDDD is to be implemented via national authorities in all member states and enforced in a coordinated manner across the EU.

Which companies must comply with both laws?

Until Germany has transposed the EU Supply Chain Directive into national law, the LkSG will remain the most important benchmark for affected companies. This primarily affects companies that have been subject to the LkSG since 2024 due to the threshold of 1,000 employees.

At the same time, it makes sense for large companies and groups to set up their processes now in such a way that they cover both sets of regulations in one system wherever possible. In practice, this means a joint risk analysis, a standardized system of measures and complaints as well as a consistent data and verification concept. Additional modules are only required where the CSDDD goes beyond the LkSG. For example, the EU-wide scope logic, the broader environmental scope and, depending on the final outcome of the omnibus procedure, climate plan and liability issues.

Opportunities and challenges in implementation

Opportunities: competitive advantages through sustainable orientation

Companies that not only "tick off" the CSDDD but also use it as a management approach can benefit noticeably. When processes and supply chains are better managed, waste, rework and delivery failures are reduced. Especially where risks were previously only noticed late. Circular design, material alternatives and greater raw material efficiency can also reduce costs because less material is used and disposal and dependencies on volatile raw material markets are reduced.

Companies can also benefit on the market: Those who can demonstrate responsible supply chains - for example, deforestation-free ones - secure access to regulated markets and improve their chances in tenders. Stable ESG structures also help to reliably meet customer requirements. They can also have a positive impact on financing conditions because investors and banks are increasingly including ESG and climate risks in their assessments. And last but not least, a clear, credible focus strengthens recruitment and employee retention.

Challenges: Practical implementation in the supply chain

In practice, it is rarely the will that is the problem, but rather the implementation in complex supply and value creation networks. There is often a lack of reliable information from lower supply levels. Data is not compatible and the influence decreases with each level. Particularly in global multi-tier supply chains, it is difficult to find, check and process data in such a way that clear decisions and measures can be made.

New processes, IT systems, training, regular inspections and supplier programs require time and budget. This not only affects large companies, but also indirectly smaller suppliers, who will have to provide more evidence in future. At the same time, traditional social audits are often not enough. They often only detect symptoms and are susceptible to "sham compliance". The whole thing only becomes effective when companies clearly prioritize, realistically introduce requirements and manage procurement more holistically - i.e. keep an eye on costs, risks and supply chain stability together.

Good change management is also crucial: purchasing, technology, sales and finance must work together, otherwise conflicts of objectives arise (e.g. price pressure versus sustainable improvements). Tools and data platforms help, but are no substitute for exchanging information with suppliers and stakeholders on site. And because the requirements have a practically global impact, many companies need to adapt their supply strategy. This can be done through diversification, more regional procurement or alternative sources of supply.

Support from external consultants and tools

Many companies make faster progress when they make targeted use of external expertise, not permanently, but to increase structure, speed and quality. This can start with the risk and prioritization logic and extend to guidelines, contract clauses, supplier programs, complaints processes and robust monitoring.

Digital tools are particularly helpful when it comes to scaling. For example, via supplier platforms, verification management, risk scores, workflow control or data sources such as satellite images for deforestation risks. The decisive factor here is not so much a single "miracle tool", but a system that fits in with the existing IT structures, is auditable and can be expanded step by step.

Pilot projects in high-risk areas that deliver quick learning effects and can then be scaled up have proven their worth. However, internal governance remains the most important factor: clear responsibilities, swift decisions and budgets that are geared towards the greatest risks and levers.

Conclusion: Why the CSDDD is the next big step towards sustainable corporate governance

The EU's Supply Chain Act turns sustainability in the supply chain into a binding management mandate. It shifts the focus away from selective audits and pure communication towards a risk-based system that works in day-to-day business: Identify risks, prioritize, act effectively, enable remediation and demonstrate effectiveness. As a result, corporate responsibility along the value chain is not only more clearly defined, but also enforceable.

For companies, this means effort in the short term - especially when it comes to setting up a database, responsibilities, supplier management and reliable evidence. In the long term, however, there is also an opportunity: integrating processes at an early stage creates more stable supply chains, reduces operational surprises and strengthens trust among customers, investors and employees. It is precisely because the CSDDD interacts with other regimes such as CSRD, EUDR or REACH that an integrated approach is worthwhile instead of isolated solutions.

It is also important to note that the legal framework remains in flux due to the omnibus procedure. Companies should therefore not wait for the "final detail", but rather set up the foundations properly now: Risk and prioritization logic, action programs, complaints mechanism, governance and documentation. Those who establish these building blocks early on will remain capable of acting regardless of individual adjustments - and will be ready as soon as the wave of applications relevant to the company starts.

FAQ

The CSDDD is an EU directive that obliges large companies to identify, prevent or mitigate human rights and environmental risks in their own activities, at subsidiaries and along relevant stages of the value chain and to facilitate remediation.

In the current text of the directive, the CSDDD applies to large EU companies and non-EU companies with a high turnover in the EU. Application is staggered (see timetable).

The EU Supply Chain Act came into force on July 25, 2024. Due to the "stop-the-clock" amendment, member states must implement it by July 26, 2027. The first application obligations start on July 26, 2028, with full application following on July 26, 2029 (depending on size class).

The CSDDD thus describes the area for which due diligence obligations apply: own activities and subsidiaries and, above all, upstream activities (raw materials, processing, production) and certain downstream steps such as transport or storage - each prioritized according to risk.

Companies must set up a functioning due diligence system: Analyze and prioritize risks, implement preventive and remedial measures, monitor effectiveness, document and provide a complaint or whistleblowing channel.

Yes, the Directive provides that natural and legal persons may submit substantiated concerns to the supervisory authority if objective circumstances indicate breaches.

Enforcement is carried out by national supervisory authorities in each Member State, which are to work together in a coordinated manner across the EU. Authorities can request information, initiate investigations and order measures.

The CSDDD relies on administrative sanctions. Fines are to be based on global net sales and can (in the current text) reach up to an upper limit of at least 5%, plus official orders to remedy violations.

The LkSG is the German supply chain law (supervision/implementation at national level), while the CSDD sets an EU-wide framework. The CSRD primarily regulates reporting, while the CSDDD focuses on risk management processes and measures. In practice, however, data and structures can be easily combined.

On December 9, 2025, a political agreement was reached to simplify or reduce thresholds, obligations and sanctions (e.g. cap on fines at 3% and narrower scope). However, these changes are only binding once the legislative process has been completed.